Jack Taylor lives in a cold, hard place – rejected by most of his peers , alcoholic, insightful, fights a lot and yet has his own integrity and a surprising kindness.

Romantic and sensationalised – but not easy

Sure, Jack is romanticised, and the stories are sensationalised. That’s TV for you. The genre is the private detective roaming around a seedy underworld, in this case, the underside of Galway. You can be sure that in every episode, he will be beaten, shot, stabbed, vilified, or generally misused one way or the other. All the tv detectives of my youth –  Peter Gunn springs to mind – had similar encounters. The difference between them and Jack, and perhaps between Jack and Marlowe, is that there is nothing of the heroic in Jack’s suffering, there is only misery. And when he fights back, he hurts too. No fist fights with nice clean outcomes, he hits hard and his knuckles hurt… he tries to protect a young boy and redeem him from a life of crime but the lad gets murdered anyway… his sidekick is shot just to make Jack suffer. There’s nothing easy in that sort of romantic.

Peter Gunn springs to mind – had similar encounters. The difference between them and Jack, and perhaps between Jack and Marlowe, is that there is nothing of the heroic in Jack’s suffering, there is only misery. And when he fights back, he hurts too. No fist fights with nice clean outcomes, he hits hard and his knuckles hurt… he tries to protect a young boy and redeem him from a life of crime but the lad gets murdered anyway… his sidekick is shot just to make Jack suffer. There’s nothing easy in that sort of romantic.

The real romance of Jack is in his integrity and kindness. While there is gritty violence, there is none of the gratuitous violent orgies of Tarantino or Nick Cave, nor the cynicism of Clint Eastwood, nor the malevolence of Scorsese. When a woman asks him to track down some person, she hands him an envelope full of money. He says with sardonic humour, “Do you want me to find her or knock her off?” as he takes only a small portion of the proffered cash. He finds a love and a sort of forgiveness towards his harsh, awful mother, when he discovers the traumas of her own life, and he cares for her tenderly after she has a stroke.

From suffering, truth-seeking

He has a deep insight into the people around him, and of course, sees the clues that those who despise him cannot. Perhaps it is true of all insight born of suffering… it is truth-seeking, while those who coast on the easy wave of conformity are deluded by their comfortable preconceptions. Yet his kindliness allows the ignorant to keep their fantasies.

The model of addiction

And the clincher – his alcoholism, the refuge of the lonely and rejected. His binges are horrible, as he staggers the streets in a blinding haze and wakes up not knowing how he got to where he is. There isn’t much romanticised in that, either. The determination to obliterate himself along with self-contempt for his addiction must have been well known, either in person or from acquaintance, to the novelist, Ken Bruen, on whose books the tv character is based. But which comes first – rejection, loneliness, or addiction? With Jack, and perhaps with others in real life, my suspicion is that it is the sense of rejection which comes first, and it is more to do with an unconventional perspective or intelligence which makes the individual feel alone, rather than with any outright rejection per se. And the judgment from others which addiction elicits only increases the misery of a person with already low self-esteem.

Well, I have never read any of Bruen’s books, but I like Jack. Some don’t like the accent with which the actor plays him – a Scottish man playing an Irish man with a thicker brogue than any of the Irish actors in the series. And the scripting is a bit hit and miss, you have to put up with some vagary here and there. But I still like Jack, uncomfortably, but then, his companions in fiction find him just as uncomfortable.

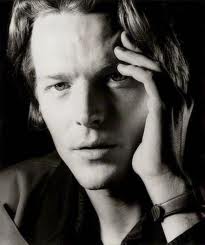

Iain Glen

I think I like Iain Glen, too. He really suits the grizzled outcast: as Jack Taylor, he is unrecognisable as the sweet-faced young actor of earlier times, who played Hamlet for instance, in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

I think I like Iain Glen, too. He really suits the grizzled outcast: as Jack Taylor, he is unrecognisable as the sweet-faced young actor of earlier times, who played Hamlet for instance, in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

Here he is imitating a chicken in that film

And speaking of that Godot-esque play of Tom Stoppard, what point do you think Stoppard was making about characters who are trying to figure themselves out when really their lives are scripted and fully determined? More on that some other time, maybe.