Shaivite Self-Realisation -Notes on a seminar with Mark Dyczcowski

Spanda is the action of Shiva – a pulsating throb of consciousness.

The tradition through which I explore Being and Reality is formally known as Kashmir Shaivism. In plain English, it means that Consciousness is itself what reality is. It is another name for reality. Neither reality nor Consciousness is inert. Consciousness – Reality – is vibrantly self-aware and creative. In Yoga, God and Reality are synonymous. After all, where could God find a home but in reality? And ultimately, you yourself are That, too.

There is nowhere outside reality that you can exist and observe reality from. You are not other than reality. God is not other than reality. There is but one reality, not a plethora of different realities, though each mind may experience that one reality differently. We call that whole Consciousness-Being-Self-Reality “Shiva”, and for the convenience of the mind, we usually personalise that wholeness, so that we consider “him” as the “Lord”, when the vastness of reality is beyond the mind to grasp. It is not essential to borrow from ancient India to find that out.

For me it has been the best of all ways to find it and to find the deepest layer of my own being. And some of the old truisms of Yoga eventually ring true. There is but One Absolute, and, the best of all, Tat Tvam Asi – you are That, That is what you yourself are. It is the yogic attempt at the Grand Unified Theory of Everything – there is only Consciousness. And Consciousness pulses, throbs in a creative urgency – Spanda.

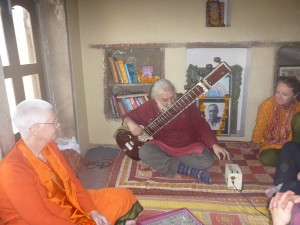

Below are some brief notes from a Skype seminar with Mark Dyczkowski a couple of years ago, (April 2011) hosted by Swami Shankarananda. Markji is an astonishing vessel of the teachings of Kashmir Shaivism. He has spent his life immersed in the Sanskrit literature of Shaivism, in an often thankless task translating not only the primary texts, but also noted commentaries of the old masters. It has not repaid him in material terms, as the job of Sanskrit scholar-sage isn’t awarded even the basic wage. Nor has it repaid him in academic honours, as a Westerner living in India is not permitted to hold a university post; yet what he has got from it has made him rich beyond all other teachers of the tradition.

The bulleted points are his, as best I remember them, though they may follow a different order from his delivery in the seminar, and the notes following are a mix of remembering enlarged by my own explanation.

The topic was a verse from an ancient Shaivite text, Verse 21 from the Spanda Karikas:

Therefore he who strives constantly to discern the Spanda principle rapidly attains his own (true) state of being even while in the waking state itself.

Spanda

Spanda is the action of Shiva – a pulsating throb of consciousness. We can recognise Shiva by his acting, and we can become aware of it by being alert to this pulsing vibration of consciousness. Shiva is synonymous with Consciousness, with God, with Reality. Not the ‘god’ of our childhood who lives in the sky and made a creation which we broke, and who rewards and punishes as he is pleased or displeased, but rather who is vitally self-aware and who is constantly creative, forming himself into an immensity of experiences, forming himself into all there is.

How God Acts

- The world and our experience is God acting to make himself known.

- He can be known if you attend constantly to his action -not to the personal items of experience but to the underlying creative action.

Shiva, Universal Consciousness, is another name for God. Not the “god” who is eternally Other; rather, god who is the sum total of reality. Yoga would have it that god creates himself as all there is. He makes himself known through his becoming. If there could be an external observer, he would observe Shiva becoming all there is. Since the only observer is you, and you are part of the becoming of Shiva, you get the opportunity to see the wholeness of who you are, if you can look the right way. That can’t be from a mind-viewpoint that posits itself as separate.

This is not as extreme as it sounds. I was in the Canadian Rockies a few years ago, and was taken on an eco-tour of some of the local phenomena. One of the places we went to was an aspen grove, several acres of aspen forest. The coach driver, an eco-wag, asked us to estimate how many trees were growing in the forest. I thought it must be a trick question, and I guessed, “one”. “Arrgh,” he said, “you ruined my joke.” Yes, one tree. Aspens reproduce by growing shoots from their roots, and the whole forest was one giant organism.

Not much different from Shiva – only a difference in scale. The whole universe is one giant Shiva. You know the One aspen tree by there being the appearance of a forest, and the tree can know it’s real being only if it realises that it is not a separate entity. You know the One Shiva by there being the appearance of a universe. Shiva has a much more interesting display of his Self, though, and it is enormous beyond comprehension.

Mark points out that to see Shiva, you have to look at the action rather than be tied up with the particulars of your own little bit of it. If the most distant aspen shoot were to think, “I’m a very special, unique and important tree, different from any other,” it would have no chance of experiencing its larger being. For that, it has to get off the delusion of its specialness. We try to make ourselves special in so many ways – by knowing more than someone else, by being happier than someone else, by being unhappier than someone else… by our life stories. To become aware of our actual being, we have to give up the feeling of having special and separate being.

God and Time

- every moment a new creation

- no time – no before or after, only now.

- he is the source, not a series.

- Shiva creates the whole world in the moment, revealing himself as he does so, concealing himself at the same time in his manifestation.

- “The immediacy of the moment is the secret hidden inside the present.”

Another spectacular aspect of Shiva is that he is not bound by time. His creativeness is a spanda, a throb, a pulse – there is, and then there is not. Mark goes further: Every moment creation is fresh and new. The moment past is totally gone, the next moment has not arisen. In this moment, he creates himself and reabsorbs himself. A spanda of consciousness and the creation is made anew. It might appear similar to the one just gone, but it is in fact, different. The old adage, “You can’t step in the same river twice” is pointing to this.

Your body has aged a little since you began reading this, and your mind has changed a little, too – neurons fired off, contributing to brain tracks either of acceptance or resistance. The manifestation of “you” is different from what it was a moment ago. But Shiva is not the creator of a series of events – he is the source of manifestation unfolding.

I find myself asking, “What is a moment?” We tend to equate a moment with a second, or maybe with the blink of an eye. But is that so in Shiva? If you could free yourself from all sense of time (and scientists will tell you that time is all in the mind) what would a moment mean? Perhaps a moment is an aeon, or perhaps it’s the blink of an eye after all. The wind blows a leaf on the vine in the garden, and now it is still – is that the passing of one manifestation and the beginning of another? Perhaps my lifetime is a moment. Perhaps a phase of it is.

Suzuki Roshi liked the term, “Zen Mind, Beginner Mind” – again pointing to the freshness of the moment. The Zen master was also pointing to the way to discover Shiva, though he would not have used that name. Mark’s way of saying it is, “The immediacy of the moment is the secret hidden inside the present.”

Mark also likes to say, again and again, that Shiva reveals himself in his action and conceals himself in his manifestation. Shaivism says that Shiva has five functions – creation, sustaining, destroying, revealing and concealing. In each moment, Shiva manifests himself as a new creation, which he sustains for that moment and then destroys, or reabsorbs to his unstructured self. If you can see his creating, you can see him; if you are lost in the manifestation, he is concealed. He reveals himself by acting and conceals himself in plain view.

The Guru Tradition in Hinduism

- Hinduism – usually approached from deity-stream, but really is a vast collective of gurus and their disciples

- God’s the guru, the guru isn’t God.

Mark points out that Hindu spirituality is generally discussed under the heading of the main deity venerated, which gives focus to the scriptural means for investigating Being. He says that it would be more accurate to see it instead as a vast collection of gurus and their disciples, as every guru teaches something slightly different from every other teacher in their tradition, no matter what deity is the focus.

To me, this seems to allow a non-Hindu expansion of a certain way of investigating the spiritual, which certainly has its origins in India, but can’t be restricted to India. My guru was born American and grew up Jewish, did his sadhana (spiritual work) in India, and teaches in Australia.

I am an Australian woman who grew up Catholic. In my personal life, I cannot really be non-Australian, my values have been formed by Catholic teaching, and my gender undeniably flavours my experience of life. Although I underwent a Vedantic ritual led by Brahmin priests to take sannyas, and I am profoundly grateful for the culture which was able to nurture my spirituality in a way that neither the Australian culture nor Catholicism could, nevertheless, I cannot be Indian and so I am not a Hindu.

Yet I have sat at the feet of my guru, as disciples have for aeons, in the model of teaching established in India. And some sit at mine, in the same tradition, of learning from one who has learnt from one who has learnt from one who has learnt from one who has awakened them to a new understanding of self.

“God is the guru, but the guru isn’t God.”

This was a reference to an old adage that God and Guru are one. Indeed, grammatically, if you say “god is the guru”, you are actually saying also that the guru is god, as the “is” evokes identity between the two. “Your mother is that woman; that woman is your mother.” The identity between the two is clear. In some languages, Sanskrit amongst them, there are two words for “is”, and only one of them would give identity in this way. English doesn’t permit distinctions of “is-ness.”

Mark might have been better off to say, if he had more leisure to consider it, something like “God permits himself to work through the guru, but the man or woman who functions as the guru is not him/herself God.” Actually, the full saying is “God, Guru and Self are One”, Self being the authenitc Being of each of us, in effect, our god-nature. The plan is that the guru has realised his/her identity with the divine, and so is God. A few outstanding examples spring to mind – Jesus, the Buddha, Nisargadatta Maharaj, Ramana Maharishi, Meister Eckhart, and others, from every tradition, men and women, the high-born and the lowly.

Yet all of them were just living their human lives. It is not so much that they became god and stopped being human, but rather that they saw through the illusion of the personal, the sense of “I” that is created by the mind, and found the bedrock of consciousness which is their Self. Nisargadatta Maharaj said, “Liberation is not of the person; liberation is from the person”. Some of them liked to talk about themselves in the third person (e.g. “this one”) to avoid re-personalising their sense of being. Ramana talked about the substratum of consciousness to be discovered when the personal sense of self falls away. Not all gurus reach the pinnacle, however.

Some cannot quite drop personal egocentrism. They can still be very effective. The personality quirks of a guru can become sources of tapasya or sadhana for the seeker – it depends on how the seeker sees it.

And often people like the idea that their guru is divine – great masses of devotees might attend their satsangs. There may be an air of confidence about the “divine guru” which inspires others, and that inspiration really does bring about a shift of awareness for many of them.The point is that, after your attention is awakened, whatever your guru is like, it is you who has to do the spiritual work. Even the most nurturing guru can’t do it for you.

The Guru can Evoke Shaktipat

- Shaktipat is descent of grace, not a possession nor a passing of power.

- The grace to attend to god’s existence.

- Diksha (formal initiation) isn’t necessary.

- Swami Shankarananda: shaktipatevadiksha, “shaktipat certainly diksha”, i.e. the descent of grace is itself initiation.

- The guru is necessary.

Amongst many guru-disciple communities, including Shaivism, it is a given that the guru initiates the disciple into the spiritual life by giving shaktipat. Shaktipat is the bestowing of grace, often regarded as the transmission of power. And the guru gives shaktipat. It assumes a fair bit of authority to the guru. S/he has access to the Shakti, a line to god’s power, and s/he can confer it on you.

Diksha is is a formal initiation ceremony. Imagine my guru’s discomfiture when Mark proclaimed that diksha is not necessary, i.e. that no one needs to be initiated into relationship with god’s grace. Swami Shankarananda retrieved the situation by quoting a statement that his own guru used to make: “Shaktipatevadiksha – the descent of grace is itself initiation.” The question of whether service to a guru is required to get that descent of grace remained unexplored. Mark conciliated by saying that a guru is necessary, otherwise one’s attention is never turned away from the mundane, that the guru can evoke shaktipat, and the grace of shaktipat is the grace to seek out, attend to, become diligently aware of, God revealing himself.

So what prompted Mark to make his somewhat anti-guru comment in the first place? Since no one asked him, I can only speculate. Was it his understanding from years immersed in the texts of Shaivism? But they were pretty well all written by active gurus with the support of their disciples. Or was Mark perhaps focusing on the Shaivite tendency towards rejecting convention and social structure?

It is certainly the case that Shaivism is an iconoclastic tradition that reacted against the hieratic dominance of the Brahmins with its formulas, rituals, temples and social restrictions. It opened spiritual practice to all, including women and outcasts – with the understanding that Shiva (universal consciousness, divine presence, God) is immediate and present and that it is at best a myth, at worst a blasphemy, to wish to control and mediate the immediacy of that omnipresence, or to imply by any means that one individual is less Shiva than another. And no one owns the Shakti (grace), much less the keys to the door of God’s abode. The guru is not “the chosen one of God”. And yet, the guru is necessary, at least for a period. Traditionally, that period is 12 years, sometimes more.

Human Life – Discovering Shiva

- We are capable of intuiting infinity.

- Feeling – glad, sad or indifferent.

- In the guna system we feel.

Yogis tend to say that it is a blessing to take a human birth. Mark has a lovelier way of putting it: “We are capable of intuiting infinity”. The curious thing is that, at least on this night, he put that capacity for intuiting the infinite in the realm of feelings. It is curious because he has spent a lifetime reading and studying, which is the work of the intellect.

Yoga allows for three streams of approach to the spiritual, or the infinite – jnana, the mind and intellect, using the mind to penetrate the mind; bhakti, devotion and feeling; and karma, activity without interest in personal reward. Mark must have felt in bhakti mode at the time, whereas the great 7th Century reformer Shankaracharya said, in the Viveka Chudamani (Crest Jewel of Discrimination), that the “sheath” of intellect is closest to the experience of God. Even the word Buddha, usually given as “The Awakened One”, really means more literally, “The One with the (Right) Intellect”. And the early Shaivite masters were writers of high intellectual acuity.

But to feeling: Mark said that in general our feelings can be classed as glad, sad, or indifferent. He related our feeling capacity to the ancient belief in gunas, which were thought of as world energies out of which every existent thing is formed, including the individual. Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras mentions gunas more specifically, and in Sutra 4:32 points out that on liberation from the personal self, we are no longer at the mercy of them. In fact, the gunas are not generally described as “glad, sad or indifferent”, but rather as “inertia, action and sweetness”.

OK, but so what? Where is the Shaivism, the Spanda? I wonder if Mark was doing a little dance with my guru, his host, instead of extrapolating the text that was the topic of the night. Swami Shankarananda makes feeling-awareness central to his teaching, saying that it is how you experience reality. It is a powerful and transformative practice, and great credit to him for introducing it into the satsang. Personally I believe it is not quite enough. We are thinking, feeling, doing organisms, and we accumulate a mass of assumptions, habits and expectation from which the present feeling arises. One has to enquire a bit more deeply into them, not only what one is feeling at the moment, to the exclusion of everything else.

Anyway, the point is that I doubt that Mark was pointing to any specific teaching in Shaivite literature, so I can only assume he had been reading to see what Swami Shankarananda teaches. Perhaps compensating for his earlier gaucherie about the role of the guru.

Penetrate to the Heart of Being

These last few points were brief, in response to questions from the audience.

- Enter reverently into our own heart – there we find the ground and foundation of all Being.

- Meditate to bypass the mind’s constructions.

- Aesthetic bliss enables us to recognize the divine bliss, and then that leads up to be able to find bliss in the less beautiful.

Hridayam (the Heart)

In Shaivism, hridayam, the Heart, means the core of consciousness, the centre of our being. There is no romantic association with the heart, not a love-heart or the beating heart. It is the central core of Self, more likely to be associated with a lake or sea of consciousness than a Valentine. Mark says that we have to have reverence for that core of our being. Patanjali, too, says (YS1:14) you have to persist with reverence and respect for a long time. That reverence and respect is directed at the core of your being, not at an external person or object or a mental concept of “God”. That reverence, in Shaivism, is not about ritual and liturgy and priesthood, it is about reverently penetrating your own sense of being.

It is not an ordinary approach to self, is it? We generally take ourselves for granted, and suppose that someone called “I” somehow owns a body and mind, and we are rather stupidly unaware as the days of our life unfold. Having reverence for the very act of being, recognising that really knowing your being is to know infinity, suddenly gives a new weight to the unfolding of our days.

Yoga says that if you can penetrate your own mind, look past its tendencies to create the “this is me, you know!” you will find the substratum – pure consciousness without any mind structures in it, and that is your Self. You find that the person you thought you were is only one of those mind structures, and all of your ideas about how things ought to be are just mind structures, and with a cry of surprise you shout, “Hey, that me was an illusion, this is who I am!” Unstructured reality, pure consciousness. And while it hasn’t got attributes, its intrinsic nature is creative, loving and intelligent.

Meditation:

Meditation is essential in penetrating through mental structures. The mind is so convincing in treating its own ideas as what reality is, particularly what the reality of what Self is, that it is improbable if not impossible to see through it while it continues the same old game at every minute of every day. So meditation certainly means Stillness. Keeping the mind still. And at the very least, even if that chatter continues in some of your meditations, position yourself in the awareness that the mind is doing the chattering – rather than dancing with the chatter. Visualisation is rarely useful in this, as it has the mind doing a bit more of the same old thing, creating imaginary worlds – it doesn’t help at all in the task of seeing through the mind’s processes.

Aesthetic Bliss:

Almost everyone occasionally feels the sense of wonder or divine presence as an aesthetic response. It could be when in the beauty of nature. Some poets, Wordsworth for instance, have written extensively on losing their ordinary sense of self and being lost in wonder and awe on such occasions. Here Mark was saying that it is easy to have those feelings in response to the sublimely beautiful, and that is our opportunity to recognise the spanda, the throb of Consciousness. From recognising it in response to the aesthetically beautiful, we little by little develop the same response to those things that are not aesthetically pleasing.

My guru’s guru, Muktananda, used to admire a sadhu named Zipruanna. This sadhu went completely naked with no possessions, and his home was a rubbish dump. And they say that he was always in a state of delight and satisfaction. So next time you come across something rather foul and ugly, see how your aesthetic response handles it. If you turn away in disgust, remember, Shiva lives there too, and it is your mental construct rather than your Heart that is offended.